The missing foundations of cybersecurity marketing

Cybersecurity marketing is in a weird place.

A function we all know is essential, particularly to achieve the kind of growth demanded by venture capital firms, has been relegated to the incremental task of “generating leads” for sales.

I say we all know marketing is essential because we do. Better marketing = better business.

We’ve seen it a million times.

We all have closets and cupboards full of branded goods. We’ve heard that “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM” and understood its truth and the reasons behind it.

Why do some vendors explode while others languish in irrelevance? It can’t be explained purely by the quality of their solutions. Several factors are at play, and marketing is one of them.

But most business leaders don’t understand the mechanisms involved in good marketing. And what they’ve seen over the years from marketing departments has led them to despair of ever benefiting from it themselves.

So here we are. Cybersecurity marketing teams are glorified BDRs with big budgets and unattainable performance targets.

Naturally, there’s plenty of noise and blame-throwing going on, and no shortage of people proposing solutions. Often, VERY LOUDLY.

When I speak to marketers, they tell me:

“Our targets are disconnected from reality”

“We’re sick of being lapdogs for sales, who never appreciate us anyway”

“We struggle to stand out in such a crowded market”

“Business leaders don’t understand marketing”

“We spend most of our time trying to meet KPIs that don’t serve the company’s interests”

When I open LinkedIn or go to conferences, I hear all sorts of suggestions about how to fix this:

“Just do better messaging”

“We’ve got to be data-driven”

“Marketers should focus on brand”

“We need more and better content”

“Gotta have sales alignment”

And this is just a taste.

Marketers get no support from SMEs. Founders want to see concrete results. Marketers have heard they should speak to customers… but half the time, they aren’t allowed anywhere near them. Brand. Email. Messaging. Customers. KPIs. ABM. Insights. Sales. Revenue. Pipeline.

The problems and solutions are seemingly endless… and all the while, people are being laid off and leaving the industry at the fastest rate I’ve seen in my 11 years as a cybersecurity marketer.

But here’s the thing.

While painful, these are symptoms of the problem. They aren’t the problem itself, and worse, they don’t clearly point to the real problem.

The missing foundations of cybersecurity marketing

So, what is The Big Problem with cybersecurity marketing?

My thesis is this: marketers have become obsessed with marketing operations while forgetting about marketing foundations.

(It’s actually worse. Marketing teams have become obsessed with promotional operations at the expense of literally everything else. We’ll come back to that.)

What I mean by foundations is all the information gathering, groundwork, and planning necessary to conduct operations in a focused, intentional, and effective way that supports business objectives. Not exactly revolutionary, but very definitely missing en masse from the cybersecurity industry.

Here’s a visual metaphor.

Consider the Parthenon: a temple in Athens, Greece. You probably recognize it.

Source: Britannica

Nice, right? It turns out if you want to build a temple with 100,000 tons of marble — and have it still standing almost 2,500 years — you need some pretty strong foundations. This is what they look like:

Source: The Acropolis in the Age of Pericles, Jeffrey M. Hurwit (loc.gov)

Reportedly, in some places, these foundations are around 1.5 times deeper than the height of the building above. I’m no expert, but I’d imagine the solidity of these foundations may be part of why the Parthenon is still there after nearly 2.5 millennia.

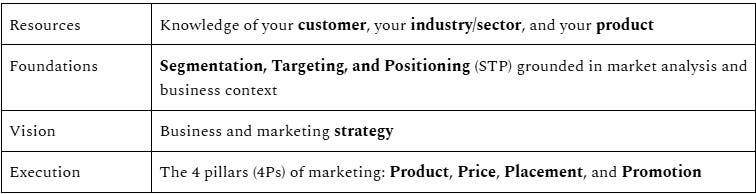

If you want to build something big and impressive, you need four things: material resources, solid foundations, vision, and execution.

In the context of a cybersecurity marketing program, this means…

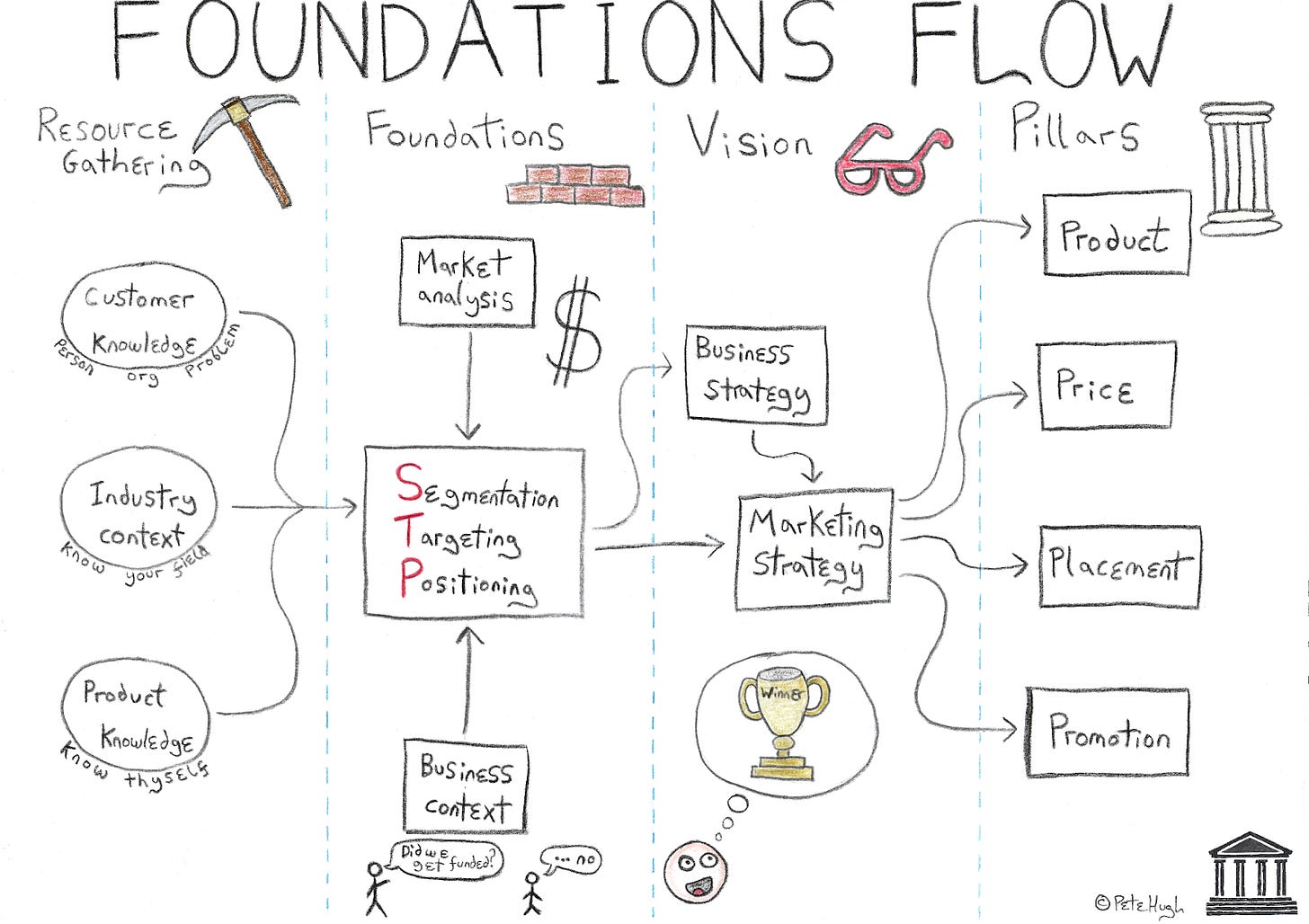

The diagram below shows how this all fits together, with the help of my child-grade drawing skills.

When I talk about marketing foundations, I’m really talking about the first three columns in this diagram. Every cybersecurity marketing team has execution — even if it’s often limited to promotions — but a great many pay only lip service to resources, foundations, and vision.

Of course, my diagram is oversimplified. The real world is rarely this straightforward. Still, as I walk through each of its components, hopefully it will become clear why each column rests on those that came before it — and that a lack of any one component will inevitably harm the final result.

Let’s get into it.

Resource gathering: Something doesn’t come from nothing

What resources do we need to get started? Quite simply, knowledge.

I’ve been in the cybersecurity industry for 11 years. During that time, I’ve met…

Tons of highly competent marketing operations people.

Many great product marketers.

A decent number of excellent strategists.

Some marketers with a really solid grasp of marketing theory.

But marketers who have the necessary skills for their function plus a strong grasp of their customers and the industry/sector they occupy? I’ve met less than five.

Keep in mind, I’ve worked with more than 70 cybersecurity companies and hundreds of marketers. For all that, I’ve met a single handful of people who possess all of the raw materials needed for effective marketing. Oddly enough, they’re in extremely high demand.

But I’m not here to malign people. I’m here to explain why this is a problem.

Across the board and in almost every field of human endeavour, there has been an industrial-scale rejection of genuine knowledge in favor of synthetic “insight”. In marketing, this presents as the wholesale embracing of MarTech and AI tools designed to replace learning, thinking, and understanding with the passive acceptance of superficial ideas, half-truths, and comfortable lies.

It would be funny if it weren’t so harmful.

I have more to say, but this isn’t the time. If you want to go down that rabbit hole, check out Clark Barron’s work. For now, it’s enough to say that what cybersecurity marketers really need is knowledge.

Not data. Not information. Not “insights”. Not AI sludge.

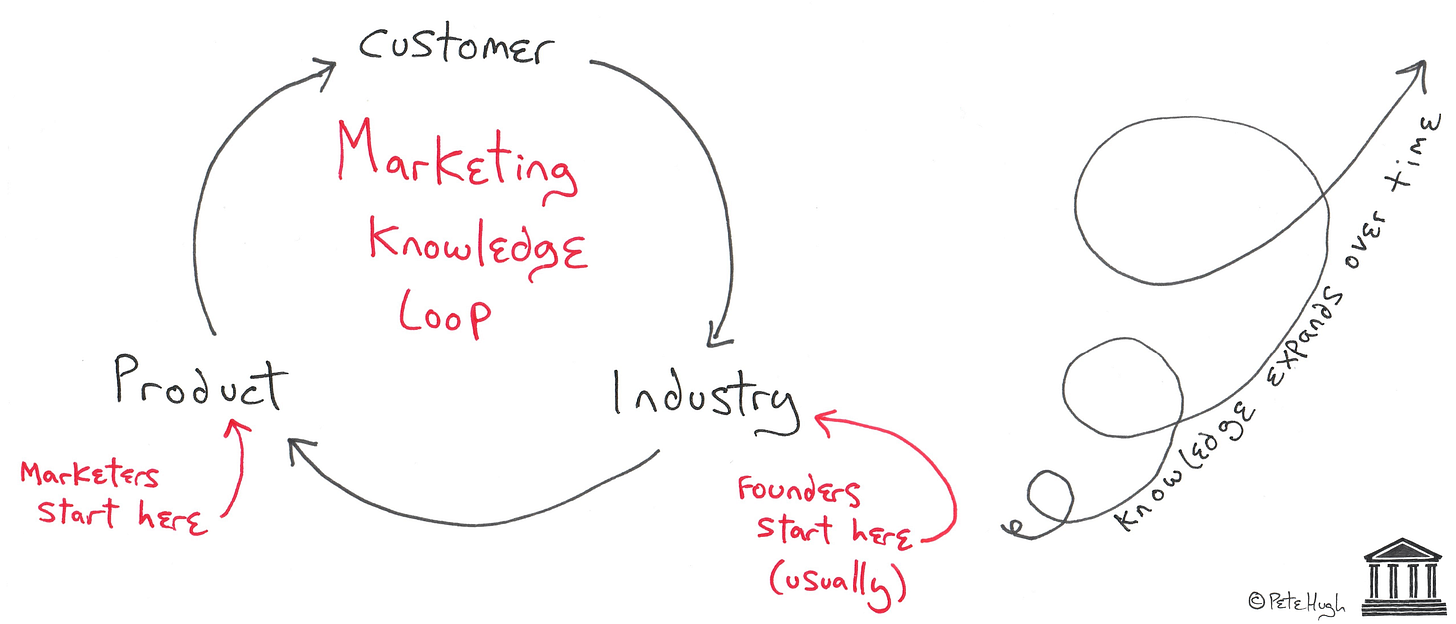

Actual, in-depth, real-world knowledge. Specifically, in three areas:

Customer

Industry context

Product

I’ll go through the basics of each here. There will be a lot more on these in the future.

Customer knowledge is essential. If you don’t have it, you’re dead in the water.

And I’m not talking about “Cedric the CISO” style personas. This is what most marketers are used to, and these documents are rightly and universally reviled.

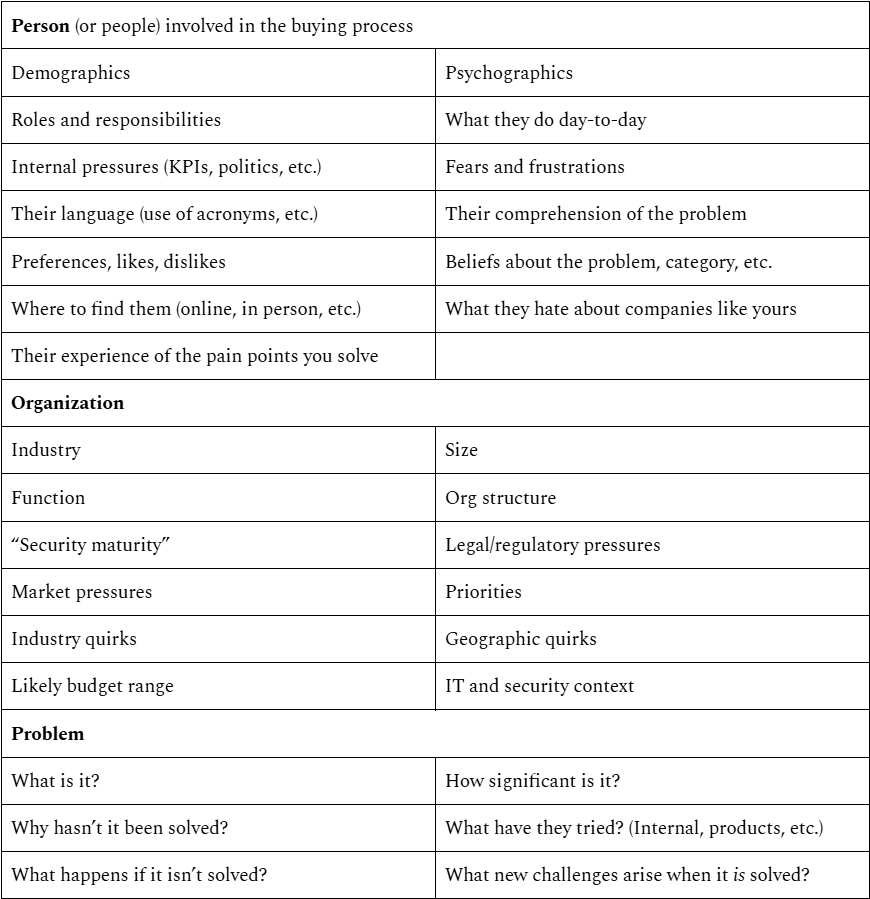

Customer knowledge can be broken down into three categories: The person (or people) you sell to, the organizations you sell to, and the main problem your product solves. That’s it.

Person. Organization. Problem.

Simple. It looks something like this:

I can hear some of you groaning: “This is too much… How is org structure relevant?!”

It may not be.

But let’s say you’re selling to hospitals in the US. Many have IT departments that are organized quite differently from similarly sized organizations in other industries… and it matters very much if you want to sell them certain types of products.

The table above isn’t exhaustive. It’s illustrative. In practice, you’ll figure out what you need to know by rolling up your sleeves and getting to work.

Industry context is simply gaining an understanding of the space you inhabit. Honestly, this barely happens in cybersecurity marketing, and when it does, it’s often done in a misguided way.

Understanding the space you inhabit isn’t about getting certifications or doing an ethical hacking course, though you may find that helpful. It’s about understanding the logical processes, forces, motivations, and pressures that make up the “stuff” of your industry and sector, as well as the concepts and theories that guide them.

This is something people miss when it comes to IT. No matter how many 1s and 0s it’s wrapped in, there is always a process. Software and hardware aren’t magic boxes that spit out answers. They’re bundles of processes that can be understood and explained… often fairly simply. You don’t necessarily need to be able to do the operational processes, but you do need to understand how they work and what they achieve.

The same goes for security.

Security is a distinct field with its own body of theory and practices. It can be implemented in an IT context, but it isn’t just “part of IT”. If you really want to understand the space you’re in, it would benefit you to look beyond “cyber” and learn the basics of security.

Here’s a list of knowledge categories you may want to investigate. Again, it’s not exhaustive.

You’ll notice that this goes beyond IT and security, and way beyond the confines of the specific sector your company occupies.

It’s a lot, and I can only say you didn’t pick the easiest industry. I’ve been doing this for 11 years, and I can have a sensible conversation with pretty much anyone about pretty much anything to do with IT security and a bunch of related fields. This is only because I’ve spent thousands of hours learning, writing, and talking about it.

Great Big Important Note

I put customer knowledge first on the resource list because everything we do is ultimately for their benefit. But… if you can’t hold up your end of a conversation that spans a range of interconnected topics, often including some that aren’t directly covered by cybersecurity, your customers and prospects WILL NOT open up to you.

They’ll see you as “just another marketing numpty” and you’ll get the bare minimum from them. Worse, you probably won’t even realize it.You don’t have to know as much as a practitioner about their field of speciality. I don’t. But you do need to know enough to ask the right questions, understand the answers, and dig deeper where necessary.

The good news is if you structure your learning sensibly, you’ll know more than 99% of your peers within a few months.

OK, that’s enough. Moving on.

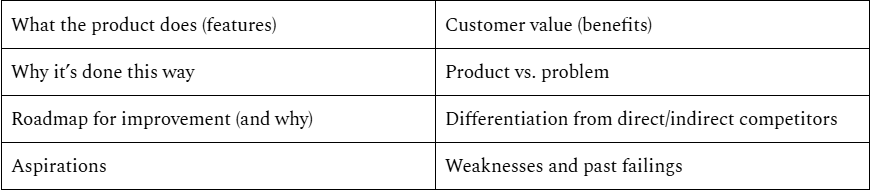

Product knowledge is precisely what it sounds like. This is where most marketers start, and understandably so. It sets the context for everything else.

If you don’t know what your company does in great detail, you’re going to struggle.

You can start with:

That’s the basics of gathering information resources. As you might expect, this stage is continuous. Gaining more knowledge in one of these areas will help you gain more knowledge in the others, in true virtuous cycle fashion. Something like this:

Before we move on, I want to share a few thoughts that might help you along the way:

I want you to reject the idea that technical concepts are “too complicated for marketers,” or that learning this stuff isn’t your job. They aren’t, and it is.

I see a lot of talk about marketing “getting a seat” at various tables. Understand that it’s not always departments that get a seat… it’s people. If you demonstrate competence, there’s a good chance you’ll get asked to be involved.

Attempting to completely eradicate wasted time from the information gathering process will inevitably cause you to miss something important. Not everything you learn will be usable, but equally, some things that seem irrelevant may prove extremely valuable.

Foundations: Because building stuff on sand doesn’t work

I contend that the foundations of cybersecurity marketing are Segmentation, Targeting, and Positioning (STP) grounded in market analysis and business context.

That’s a lot of big words that basically mean: you need to know who you’re trying to sell to, where to find them, and what value you have to offer them… and you need to be sure your choices are suitable in light of your objectives, market conditions, and the current state of your company.

I understand that “STP” comes loaded with a ton of negative sentiment and experience. Last week, I had a conversation with a cybersecurity marketer where I mentioned STP. Her response:

“STP - now that's real MarTalk!”

Look. When something is done badly for long enough, it becomes associated with that badness. This is why many marketers hate customer profiling… because every persona they’ve ever seen was unusable. But doing something badly and getting bad results tells you nothing about the thing itself.

STP is not MarTalk. It’s the foundation of marketing, the literal groundwork that underpins every marketing output.

And, like brand, it exists whether or not you do it intentionally.

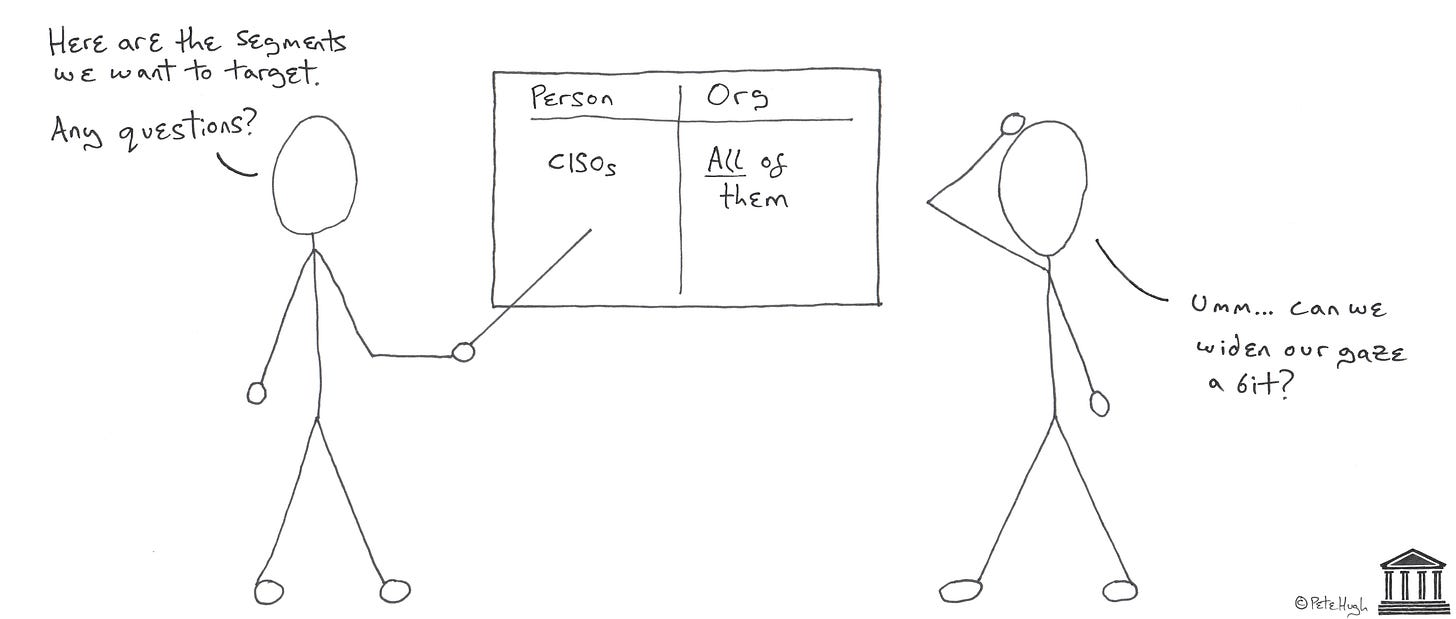

Targeting everyone with a mediocre value proposition is an STP decision. Usually not a very good one, but an STP decision nonetheless.

I’ll write more about this in the future. For now, I’ll explain what I mean and why it’s important.

Segmentation is the process of dividing your potential market into smaller, defined groups with similar needs, characteristics, pain points, behaviors, accessibility, etc. In the cybersecurity industry, this is typically done by industry, location, and regulatory coverage, but there are other options.

Targeting is about assessing and selecting one or more segments to focus your energies on. Some vendors go so far as to build their products around specific segments, but more commonly (though not necessarily correctly) targeting just informs messaging and promotion.

Positioning is… hard to define. Though many experts have tried, I’ve never found a definition that I think truly grasps the essence of what positioning is and why it’s important.

April Dunford talks about “positioning as context” in her book, Obviously Awesome. She states that “products are exceptional only when we understand them within their best frame of reference” and contends that this is achieved with positioning.

Ever the pragmatist, David Ogilvy defined positioning as "what a product does, and who it is for".

Kotler and Keller define it as the “act of designing the company's offering and image to occupy a distinct place in the mind of the target market”. This is similar to definitions given by Al Ries and Jack Trout.

Mats Georgson talks about Demand Point Constellations (DPCs) as a key element of positioning. It’s a great concept that builds on common techniques. If you haven't already, you should absolutely check out Mats’ analysis of 150 rapidly growing companies (spoiler alert: they didn’t do it with promotion alone).

It’s all in the mind

Ries, Trout, Kotler, and Keller are right when they say we’re trying to position our products in the minds of our target market… but that’s something we can only influence and not control. More on this another time.If I’m forced to pick a definition, I’m going to slightly amend David Ogilvy’s:

“Positioning is what a product does, who it’s for, and why they should care.”

More than this, positioning is the distillation of everything we’ve done up to this point. You can’t hope to position a product effectively if you haven’t acquired the knowledge we discussed in the last section — and you certainly can’t do it without segmentation and targeting.

Finally, positioning usually includes a high-level messaging component. Part of the work of positioning is determining what value you have to offer, and it’s difficult to do that without turning it into words. These might not literally be the words you share with your market down the line, but they will at least be the heart of it.

After positioning, you will know what you want to say, even if you don’t yet know how to say it.

Finally, we need two more components: market analysis and your business context.

In an ideal world, we’d sell our stuff to the widest possible market. So why don’t we?

It’s partly because building products for “everyone” often results in something that’s of limited value to any one individual. But it’s not just this.

It’s also because we don’t have unlimited resources — we can only effectively market and sell to a limited number of individuals and organizations. For companies that aren’t in a leadership position within their sector, STP is a way to maximize the utility (read: growth) of limited financial and operational resources.

So why are market analysis and business context important?

Well, you probably have internal targets. You may also have pressure from investors to achieve a certain amount of growth. Given this, the segment(s) you propose to target must be:

Large enough to sustain the growth you want to achieve; and,

Small enough that you can target them effectively with your resources and infrastructure.

Naturally, as you achieve growth, you may revisit your STP to reflect your new position in the market and (hopefully) greater resources. This is how Salesforce gained a foothold in a highly competitive industry, and we all know how that played out. In this industry, Asimily is a good example of a vendor that started with a narrow focus (US healthcare) and widened its gaze once it had achieved growth.

So that’s the foundations.

Before we move on, I will note that there is some iterative-ness between resource/knowledge gathering and STP. You don’t want to squander time learning about customers and segments you aren’t going to target, but to some degree it’s inevitable. There’s a high likelihood that some of your efforts will be “wasted” on segments that looked promising but ultimately aren’t.

Vision: You need a destination to know if you’ve arrived

Strategy is a massive topic, and we’re hardly going to cover it here. Again, this is something I’ll write about (probably at great length) in the future. For now, there are a few things to understand.

First, business strategy and marketing strategy are two sides of the same coin. You can’t logically have a strategy for a single business function if you don’t have one for the business as a whole. At the same time, your STP outputs are only meaningful if they influence your overall business strategy.

For instance, the decision to target specific market segments doesn’t just affect marketing, it affects the entire company.

Your proposed positioning can and should influence how you develop your product over time, and that’s the primary source of your company’s value. If all those knowledge resources you’re gathering aren’t being used to improve the company as a whole, they are being severely underutilized.

In short, marketing and the business are inseparably connected, and trying to create a marketing strategy in isolation is a highway to producing a document that gets filed away forever and never looked at. This, unfortunately, is the fate of most strategies.

Second, while strategy is notoriously difficult to define, a good strategy is quite easy to recognize. If positioning is context, strategy is direction. It should:

Set out what you’re trying to achieve

Define the space you hope to achieve it in

Provide a broad outline of your approach

Get out of the way and let people do their jobs

You don’t hire people so you can micromanage their every move. A good strategy sets the direction for operations, and gives the operators freedom to act as they believe is appropriate to take the company in that direction.

From there, KPIs are the tool we use to check whether we really are moving in that direction, and if we’re moving at an acceptable pace.

One of my biggest bugbears about KPIs is that they are often chosen “because this is what everyone does” rather than to guide operations and determine effectiveness against clear success criteria. I’m not going to get into KPIs and performance tracking here, but suffice to say, you don’t choose KPIs until after you know what you’re trying to achieve and have set your direction.

Finally, while STP isn’t a strategy in itself, it’s a major component. If you have sensible outputs from your STP process, you already have a better strategy than most of your competitors.

A typical strategy for cybersecurity vendors is “we’re going after the enterprise.” Aside from the fact that this isn’t a strategy, it’s also generally based on the dubious assumption that winning a small number of large accounts is the best path to growth. That may be true, but it usually isn’t, and it’s almost never helpful.

Still, this is what you’re up against.

Pillars: The 4Ps of marketing

So the foundations are in place. Now we can build something on top of them.

This is where the pillars — the 4Ps — come in. Everything up to now is designed to support operations in these areas, just as the Parthenon’s pillars rest on countless tons of stone foundations.

We’re out of the realms of foundations, so I’ll keep this part short.

Marketing should at least influence all four pillars.

Product isn’t owned by marketing. That ship has sailed. But it should be influenced by marketing. If not you, then who? Software developers and security practitioners are not the experts in your customer’s problem — you are. Or, at least, you should be.

Price is treated like voodoo and generally done badly. Most companies just “do what everyone else is doing,” not realizing that their competitors are also trying to copy them. Price is now completely severed from marketing at many cybersecurity companies — a trend I’d like to see reversed.

Placement is a weird one. Performance marketing is kind of like physical availability for digital and remotely delivered solutions, so in a sense, marketing does own it. Placement might also include partner and channel strategies, which may or may not be owned by marketing.

Promotion is clearly owned by marketing — in fact, it’s all that many marketing teams do. Do it in line with your strategy, keep building your knowledge resources, and always keep your STP outputs at hand to guide your approach.

Allegedly, there are now more Ps: Purpose, People, Pandering, and so on. Forget about them. They are either:

Already covered by the 4Ps

A strategy consideration

Irrelevant

Finally, there are strategic elements to each of the pillars. If you decide it’s important to have a defined strategy for one or more pillars, make sure it’s in line with your higher level strategy and follow the principles from the previous section.

Wrapping up: You can’t just treat the symptoms

If the Ancient Greeks had built the Parthenon on poor foundations, it would have collapsed a long time ago, and we’d never have heard of it. This is similarly the fate of a disappointing number of cybersecurity vendors — all of which, I assume, were launched with the best intentions and a cool product to sell.

More commonly, though, cybersecurity vendors with poor marketing foundations don’t fail… they just chronically underperform.

It’s actually quite difficult to go out of business in a market that has grown at a staggering rate for two decades and is awash with venture funding. On the other hand, it’s very easy for a vendor to limp along, never quite achieving the growth and recognition it could potentially have.

I should know. I’ve seen it over and over for the last 11 years.

That’s why I wrote this article. I’ve seen the inner workings of more than 70 cybersecurity marketing teams. I’ve seen what works, what doesn’t work, and what differentiates successful vendors from chronic underperformers.

And frankly, I don't believe I've said anything controversial here. It's just this:

Product, Price, Placement, and Promotion are the pillars of marketing. Everything we do falls under one of these.

You can't do them effectively or monitor your success if you don't have a strategy. What does "effective" even mean if it's not measured against anything?

Your strategy will suck if you don't know who you sell to or what value you provide. Arguably, you shouldn't have a business if you can't answer this.

You can't know this if you don't understand your customer, industry, and product. Something doesn't come from nothing — you need raw materials.

This also explains why treating the symptoms of failing marketing doesn’t work:

Tighter messaging? Okay, but for whom, about what, and why should they care?

More focus on brand? Sure, but again, who do we target and what’s in it for them?

Better KPIs? Absolutely. But what are we trying to achieve, and how do we know it’s sensible?

And the ever popular (unspoken) assumption: “We just need to do more and better”.

Well, knock yourself out, I guess. It’s worked so far, right?

Business is fundamentally about value exchange. Marketing is supposed to facilitate the exchange. This is what the 4Ps are all about. But marketers can’t execute on the 4Ps without raw materials (knowledge), foundations (STP), and vision (strategy).

So what now?

Well, if you’re a cybersecurity marketer, I’d encourage you to start gaining relevant knowledge and speaking to your business leaders about the need for stronger foundations.

If you’re a founder, I want you to understand that marketing isn’t just about promotion — it’s the entire process of exchanging value with an appropriate target market. If you treat it as “just promotions”, you’re very likely hamstringing your chances of achieving growth.

And if you’d like some help…

Well, this is what I do. I build cybersecurity marketing foundations.