Why cybersecurity buyers don't buy (from you)

What cybersecurity founders should know about marketing: Part 2

"They're just not seeing the value we have to offer!"

This is a common sentiment among cybersecurity founders. And it’s easy to understand why.

It’s frustrating to watch prospects line up to buy clearly inferior (and more expensive) products from larger vendors. Yet they do it over and over while ignoring smaller vendors.

And in the case of truly new products with no direct competitors? It’s even more frustrating. Frequently, exciting startups are ignored altogether by their intended market, despite their ability to address clear and present pain points.

Surely, if prospective customers truly understood the value your company had to offer, they would gladly pay for it… right?

What is value in B2B cybersecurity?

Generally, if your prospects aren’t buying from you — or they aren’t buying your solution category at all — there’s something deeper afoot than not recognizing the value you have to offer.

Why do B2B buyers consistently buy suboptimal products and services from big vendors when there are readily available and more valuable alternatives?

Is it an issue with the way buyers perceive value? For that matter, what is value?

Here’s a simplistic (and incorrect) model of how buyers perceive the value of B2B solutions:

Value = Benefit - Cost

So, let’s say a solution will make (or save) an organization $100k per year and it costs $20k per year. That’s a solid $80k per year of value.

If this were really how organizations behaved, buying processes would be simple.

Trouble is, this model fails catastrophically to explain what happens in the real world.

Even if we consider that Cost is much more than sticker price (it has to factor in implementation, training, loss of productivity, opportunity cost, etc.) reality simply does not support this model of B2B buyer behavior.

Specifically, it doesn’t account for two things:

Why so many (>40%) of B2B purchasing processes end in no decision.

Why large vendors win most deals even when their solution is inferior.

If the issue was purely that buyers don’t perceive value in a solution category, there would be no purchasing process. Either buyers would perceive the value and make a positive purchasing decision (regardless of which solution wins) OR they would not perceive the value and there would be no purchasing process. Organizations don’t commit time and resources to a purchasing process unless they are pretty darn sure there’s value to be had.

And if solutions were evaluated purely on Benefit - Cost, the best value solution would always win.

But this is not what happens. Buyers consistently begin purchasing processes that end in no decision. They also consistently buy suboptimal solutions even when they know they’re suboptimal.

So… what gives?

To understand how B2B buyers really decide, we need to consider two additional factors:

The real most important factor in B2B buying decisions (it isn’t value)

How buyers perceive risk

Let’s get into it.

What do B2B buyers optimize for?

"In B2C decision making you're trying to minimize the risk of regret. In B2B decision making you're trying to minimize the risk of blame."

I'm not certain of the origin of this idea. I've seen it stated by Rory Sutherland, Dale W. Harrison, and several others. Regardless, it holds true.

B2C buyers want a solution that is “good enough” for their purposes, not necessarily the one that’s objectively best. This is an energy saving response, as finding the best possible product or service is generally not worth the effort. Herbert A. Simon coined the term satisficing to describe this approach in a 1956 article for Psychological Review.

In the quest for such a product, consumers will generally prefer a “safe and decent” option to one that is potentially much better but may disappoint.

As a consumer, if I decide to take up running, what are the chances I'll opt for Nike running shoes vs. a brand I've never heard of? Pretty high, right? They might not be the best, but they are unlikely to be terrible. This is optimizing to avoid regret.

Anecdotally, I am a perfect example of a consumer who optimizes to avoid regret. If I buy something and it works okay, I'll probably buy it for the rest of time or until the product is discontinued. I choose the same food items from the same places over and over because, in most cases, I’d rather be safe than sorry.

B2B buyers, meanwhile, are primarily concerned with avoiding blame. Given the choice between an "OK" solution that will be easily accepted by colleagues and a potentially "great" solution that may attract criticism, which do they choose? Overwhelmingly, the answer is the safe option.

We talked about this in my last article. If their career is on the line, most people will choose a safe-but-suboptimal solution over a risky-but-potentially-outstanding solution.

This is a big part of why so many B2B buyers choose the largest vendor... even when their product is terrible. You've probably used Microsoft Teams, or SalesForce, or SAP, and thought: "why does anyone buy this crap?!" The answer is that if you buy from a big vendor and the solution is poor, the vendor gets blamed. If you buy from a small vendor and the solution is poor... you get blamed.

"Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM", after all.

It's not because big vendor solutions are universally great. It's because they are very unlikely to blow up in your face… and even if they do, it won’t be your fault. There is quite literally safety in numbers.

As a smaller vendor, these patterns are unpleasant to accept. But accept them you must.

Risk and the stages of innovation adoption

In short, risk is a key factor in all purchasing decisions. More accurately, perceived risk.

We can see this play out rather easily by looking at macro trends.

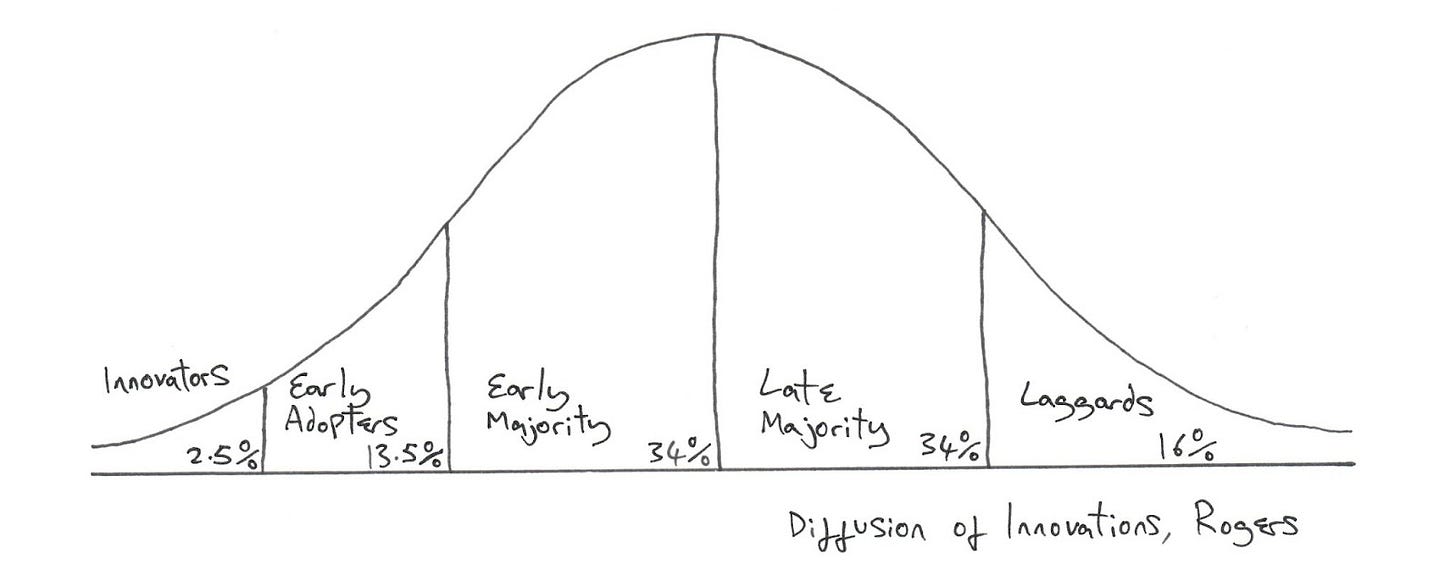

In Diffusion of Innovations — first published in 1962 — Everett Rogers provided a chart of how new innovations are adopted by different categories of buyers.

You know the one. It looks like this:

A slightly amended version of this chart (and concept) was popularized by Geoffrey A. Moore's Crossing the Chasm... but as is usually the case, it's well worth reading the original source material, even though it's based on adoption of innovations in agriculture.

Here are a few choice quotes from the book that highlight what we need to understand:

"Innovations perceived as most economically rewarding and least risky were adopted more rapidly."

"[...] the respondents in most of these studies are U.S. commercial farmers, and their motivation for adoption of these innovations is centered on economic aspects of relative advantage"

"The salient value of the innovator is venturesomeness. He or she desires the hazardous, the rash, the daring, and the risky. The innovator must also be willing to accept an occasional setback when one of the new ideas he or she adopts proves unsuccessful, as inevitably happens."

Nothing too surprising here, right?

Customers like low risk, high reward solutions, and their willingness to buy innovative products is heavily dependent on their risk tolerance.

Add this to our basic value calculation, and we have three variables that predict willingness to buy: benefit, cost, and risk. In reality, benefit and risk are both perceived more than they are calculated, while cost is generally estimated.

Innovators and Early Adopters have higher risk tolerance, while Laggards have extremely low risk tolerance. But in all cases, buyers are "running the mental maths" to determine whether the potential pay-off of a purchase outweighs the risk. It's just that their calculations are weighted differently depending on their risk tolerance… and their level of optimism.

(Rogers doesn’t use the word optimism. He describes earlier adopters as "less fatalistic" than later adopters — they perceive a greater ability to control their future.)

Notably, this research is concerned with adoption of innovation categories (for want of a better word) rather than specific products. When new buyers enter the market for an innovation, they will still seek to minimize their risk when selecting a product.

How do buyers assess risk in cybersecurity?

So, risk is an important factor for B2B buyers, and that includes cybersecurity. How do we determine how risky a buyer might consider us to be?

The first step is to understand the different types of risk a buyer perceives. Jacob Jacoby and Leon B. Kaplan laid out five risk factors in The Components of Perceived Risk (1970/1972):

Financial — risk of losing money due to a failed implementation or unexpectedly high implementation or maintenance costs.

Performance — risk the solution will not work at all, or in line with expectations.

Physical — risk the solution will be unsafe, cause harm, etc.

Psychological — risk the solution will not "fit in well with your self-image".

Social — risk the solution will affect the way others think of you.

The authors also note an additional factor presented in Consumer Rankings of Risk Reduction Methods by T. Roselius (1971):

Time loss — risk of wasted time and effort due to a failed implementation, or one that requires unanticipated adjustments, repairs, or replacements.

While these factors are derived from studies of consumer markets, it's easy to see how these risk factors carry over to B2B buying scenarios.

Social risk translates closely to professional risk ("risk of blame”) in a B2B environment. For example, buyers may suffer a loss of political capital due to a failed implementation, and potentially career-harming consequences.

Physical risk may align with "security risk" (however you want to think about that). For example, the solution could literally create risk (e.g., because it includes vulnerabilities) or it could fail to provide the stated protective benefits, providing a false sense of security.

Security satisficing and blame avoidance

If we zoom out, we may uncover another consideration. Arguably, many organizations are not optimizing for "the best possible security program", but rather for "the security program nobody can blame them for if they get breached".

What is the value of a "better" security solution if it's less well recognized by the industry at large? An organization may in reality be "more secure" but that's not much consolation if the decisions that led there are harder to justify.Jacoby and Kaplan offer a mathematical equation to calculate overall risk based on the factors above. If you're interested, you can find it in their paper. From a practical standpoint, I believe it’s more important to understand the risk factors and how they relate to your solution than it is to reach a definite figure.

While buyer risk is a real number, it's unlikely you'll be able to calculate it accurately, not least because it's unique to individual buyers. Again, different buyers have different risk tolerances, and may also be more or less sensitive to the various risk factors.

Still, understanding the components of buyer risk gives you a chance to de-risk your solution, which will positively affect your risk-adjusted value.

It’s not about value… it’s about risk-adjusted value

When you understand that B2B buyers optimize to avoid blame, it becomes obvious why so many B2B purchasing processes end in no decision. In many cases, the decision to “do nothing” simply has a higher risk-adjusted value than any available purchase.

It’s calculated like this:

Risk-Adjusted Value = Perceived Benefit - Total Cost - Perceived Risk

Beyond the basic Benefit minus Cost calculation, we're factoring in the six risk factors described above… with the added challenge that we need to consider both risk to the buying organization and personal risk assumed by the individual(s) involved in the buying process.

When we consider this, it becomes easy to understand why so many buying processes end in no decision. It goes something like this:

Prospect perceives sufficient “raw” (i.e., non-risk-adjusted) value in a solution category.

Prospect appoints a buying group.

Buying group identifies potential solutions.

Buying group determines risk-adjusted value for solutions and the status quo.

Buying group makes a decision… often to do nothing.

Once raw value is perceived by a buyer, the purchasing process determines whether the risk-adjusted value is sufficient, i.e., whether the raw value weighs favourably against the various risks (personal and corporate) associated with making a purchase.

Risk-adjusted value is “felt” more than calculated

Generally, buyers don’t use mathematical equations to arrive at hard numbers for risk-adjusted value. Even in B2B, where purchasing is allegedly fact-based, emotion plays a huge role in the decision-making process. This is actually a good thing from our perspective, because it allows us to improve the risk-adjusted value of our solutions using both rational and emotional levers.Of course, there is usually some risk associated with the status quo. If there wasn’t, there most likely would never have been a purchasing process — the status quo is simply not painful enough to justify doing something about it. But even if the status quo is painful, the risk-adjusted value of many solutions is simply not enough to justify purchase… even if nobody is happy with the way things are.

Finally, when B2B buyers do buy, they don’t choose the solution with the greatest perceived benefit. They choose the solution with the highest risk-adjusted value.

This is why so many organizations repeatedly buy from market leaders despite knowing their solutions are suboptimal. It’s less risky, particularly for the people involved in the purchasing decision… so even if the product is worse and more expensive than the alternatives, the final risk adjusted value is higher.

Three levers to improve risk-adjusted value

Simplistically, risk-adjusted value has three components: Perceived Benefit, Total Cost, and Perceived Risk.

That means you have three levers you can pull to improve your solution’s risk-adjusted value:

Increase the perceived benefit of adopting your solution.

Reduce the total cost of implementing and maintaining your solution.

Reduce the perceived risk of your solution (and your company).

Naturally, there are better and worse ways to do each of these.

Increasing the perceived benefit of your solution doesn’t necessarily require a large investment in R&D. In fact, many vendors have invested hugely in product development, only to discover customers simply didn’t perceive the extra “value” on offer.

Meanwhile, we don’t really want to influence the risk-adjusted value of our solutions by reducing the price, because we have margins to worry about. But we may be able to reduce the total cost to the buyer in other ways, e.g., by removing pain and cost from the implementation process.

And de-risking? There are a bunch of ways to do this, and I’ll cover some of them in another article. For now, simply understanding buyer behaviour and asking these types of questions is a good way to move forward.

For a little teaser, consider this: There is clear interplay between the risk reduction value of brand power and its price elasticity benefits. These are two sides of the same coin. If you're less risky to work with, you can be more expensive and still have a higher risk-adjusted value.

Food for thought.